|

If you’re like me, the past year has been unsettling, to say the least. As someone born in Western Europe in the 1980s, I have always taken certain things for granted: we are, albeit slowly, becoming more tolerant; the wars that scarred the last century will never happen again. Barack Obama’s frequent invocation of Dr. Martin Luther King’s remark that the ‘arc of the moral universe is long, but it tends towards justice’ nicely captures this somewhat complacent attitude.

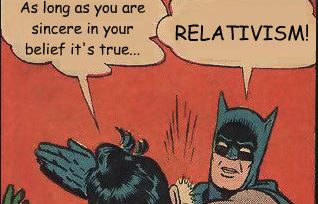

Perhaps these assumptions could never have withstood much scrutiny. But in any event recent developments have certainly cast them into doubt. The problem isn’t just that far-right populists like Donald Trump have come to power and movements with far-right elements like Brexit are enjoying a moment in the sun. Despite what some may say, there have always been politicians like Trump. Consider Silvio Berlusconi, or the bizarre career of John R. Brinkley, who used a new technology (radio) to speak directly to (and stoke up anger in) his supporters (if you want to hear more about Brinkley see this podcast). The problem is that their successes appear to involve certain common elements—a wilful (even gleeful) disregard for the truth, an ability to capitalise on (and perhaps even generate) widespread ignorance of plain matters of fact, a desire to make outsiders responsible for all manner of ills, a nascent expression of white (American, British) nationalism—that are indicative of fundamental problems, both in public discourse and in society at large. If they are fundamental problems, they require radical solutions, not a new, fresh face in charge of existing centre-left and centre-right political parties. We have been left grasping around for concepts to describe these problems. One of these concepts is ‘post truth politics’; Trump’s Counsellor, Kellyanne Conway, gifted us with another (‘alternative facts’). If we grant that these concepts describe a problem, then it is the job of ‘intellectuals’, philosophers included, to at least try to offer a diagnosis of this problem. One diagnosis that has occurred to some is that the existence of a discourse that exhibits a blatant disregard for truth and a tendency to invoke bizarre ontological categories is a symptom of a disease supposedly infecting certain parts of the academy: postmodernism, and associated forms of relativism. The problem, we are told, is that we have forgotten a simple truth: not all perspectives are equally valid. Some people are just right; others are just wrong. A good diagnosis of a problem requires two things: a well-stated problem, and a plausible account of the source of that problem. One could certainly argue that the latter is lacking here. We can (and should) grant that academic trends can and do have an impact (even a direct impact) on public discourse. But the question is whether there is much evidence that postmodernist or relativistic thinking has had such an impact. The point is not that there is no evidence. For instance, some have argued that sceptics about climate change have appealed to postmodernist ideas.* The point is rather that the evidence is, at best, inconclusive. Making the diagnosis really stick would require further investigation: What other evidence is there? How have postmodernist ideas filtered into the public consciousness? When did this happen? It would also require a comparison with alternative diagnoses; I consider some alternatives below. It is also unclear what view (or cluster of views) is supposed to be responsible. The ‘debate’ about climate change is a case in point. Recent remarks by Trump’s appointee as Secretary of State, Rex Tillerson, illustrate an increasingly common rhetorical move among climate change sceptics today. They grant the basic premise that the climate is changing, and even admit that this is partly as the result of human activity, but dispute the details, and raise pragmatic concerns about the impact of proposed changes. Maybe we are changing the climate, but who is to say that this particular model or this particular set of predictions is right? Science has been wrong before. Given the potential costs of changing our economic model, we need more evidence. Insofar as this expresses a philosophical outlook, it seems like an odd combination of scepticism and the idea, popular in some circles in contemporary epistemology, that whether you know can depend on how much is at stake. Sceptics like Tillerson challenge our claims to scientific knowledge by urging the need to weigh up the known costs of combatting climate change against the unknown costs of doing nothing; they don’t relativise anything. One could argue that scepticism is part of the postmodernist/relativist package. But then the problem is not strictly speaking a problem of postmodernism or of relativism, but rather a problem of scepticism. In any event, scepticism is hardly a new philosophical position, so there is work to be done to explain why it is part of the explanation of what is supposed to be a new problem. More fundamentally, it is unclear what the problem we are diagnosing is supposed to be. Take the idea that we are living in an age of ‘post truth’ politics, and set aside the (at best) questionable assumption that we were, until recently, living in an age of ‘truth’ politics. Talk of ‘post truth politics’ may be used to cover a range of phenomena. One thing one might mean is the tendency of politicians like Trump to make blatantly false claims; consider his first address to congress, which featured false claims about jobs, immigration, health insurance and military spending. Such claims are ‘post truth’ in the sense that they are plainly not true (though only plainly not true to those who know better; see below). Another thing one might mean is the tendency of certain politicians to make claims that are either trivially true, or largely meaningless. Consider Theresa May’s repeated insistence that “Brexit means Brexit”, or her helpful explanation that she wants a “red, white and blue Brexit”. Such claims are ‘post truth’ in the sense that their literal truth (or lack thereof) is beside the point. May wasn’t trying to communicate the trivial truth that “Brexit” means whatever “Brexit” means, or to ‘colour code’ complex international treaties. Rather, she was trying to communicate her patriotism (the United Kingdom’s flag is red, white and blue) and her intention to enact the result of the Brexit referendum. Of these two manifestations of ‘post truth’ politics, only the first could plausibly be seen as a ‘problem of relativism’. The second concerns claims that are either trivially true, or claims that don’t obviously have truth-values. But even here alternative diagnoses are possible. One diagnosis is that the first phenomenon is really just an instance of the second. It doesn’t matter that Trump makes claims that are blatantly false because their truth or falsity isn’t the point. This diagnosis makes sense for a number of reasons. It explains why Trump is rarely held to account for the false claims he makes. It fits with one of the standard responses to criticism of Trump, which is to deny that he really meant what he said. It is custom-built for Trump’s preferred medium for communicating (twitter), where it is often easier to capture attention by shocking and provoking than by careful analysis. While this may be part of a more complete diagnosis, it runs into the problem that Trump’s supporters seem to be really believe at least some of his claims. Whether Trump intends them to be true or not, they end up being believed, at least by some people. This suggests that the problem is not just Trump’s communication style but also large-scale ignorance. How has it happened that large sections of the population are ignorant of what we would regard as plain matters of fact, such as the fact that Hillary Clinton is not involved in paedophile ring based in a pizza restaurant in Washington DC, or the fact that Obama is a Christian, not a Muslim? Trump’s rhetoric works in part because he has an audience that are susceptible to it. We can’t explain their susceptibility in terms of his rhetorical style. So there must be more to the diagnosis. I would recommend that we start by asking who stands to gain from an ignorant populace. Whose interests does that serve? The answer is probably not postmodernists or relativists. I started with some personal reflections. I will finish with some more. We (I generalise from my own case) have a weakness for grand, unifying narratives. I used to implicitly accept the story that mankind is, slowly, progressing. I used to think, albeit implicitly, that the arc of the moral universe tends towards justice, though it takes its sweet time about it. In rejecting one grand narrative it is important not to yield to the temptation to replace it with another. One can tell a story where the problem today is a lack of faith in reason. One can go further and trace this lack of faith back to a mistaken (postmodernistic, relativistic) way of thinking about rationality itself. This story is attractive because there is some truth to it, not just because it is simple. Who could argue with the recommendation that we teach our students to think better? Who can deny that some postmodern thinkers have said things that might be used to justify the unjustifiable? (Some thinkers from most traditions have said things that are unwise). But this story is problematic for the same reason that most such stories are problematic. It is too simple, too neat, too in-line with our pre-existing sympathies. If we really have reached a crisis-point, the chances are that ‘the solution’ will require a radical rethinking of our existing prejudices, not simply the reiteration of values humans have clung to since ancient Greece. * Hsu, Shi-Ling. "The Accidental Postmodernists: A New Era of Skepticism in Environmental Policy." Vt. L. Rev. 39 (2014): 27.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

About UsThis is our project blog. Archives

November 2018

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed