|

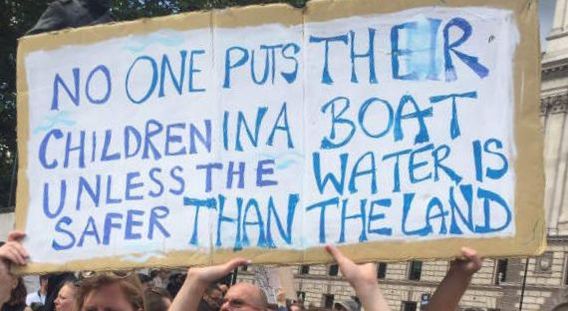

Picture credit: Ned Simmons, Huffington Post. Quote from "Home", by Warsan Shire: http://seekershub.org/blog/2015/09/home-warsan-shire/ Delia Belleri One of the most disputed topics in the contemporary public sphere concerns the extent to which nations that we identify as Western (US, Germany, Spain) should accept immigrants from countries that are politically, socially and economically worse-off. Should they impose a limit to the incoming migrants – like Austria did in early 2016? And are refugees and immigrants generally entitled to social welfare benefits – as debated in Germany last year? Answering these questions requires clarifying a number of general issues. One such issue concerns the attitude of the immigrants towards the host country. Why did they come to the host country in the first place? What are their plans as to the duration of their stay, employment and family arrangements? One common, fundamental presumption regarding immigration is that it constitutes a voluntary choice. This point is crucial in the work of a number of philosophers, because it seems to impact which rights may be reclaimed by a country's immigrant minorities. In his 1995 book Multicultural Citizenship, Will Kymlicka maintains that immigration qua voluntary choice implies the waiving of the right to live and work within one's own culture: "People should be able to live and work in their own culture. But like any other right, this right can be waived, and immigration is one of the ways of waiving one's right. In deciding to uproot themselves, immigrants voluntarily relinquish some of the rights that go along with their original national membership." This voluntary act implies a presumption that the immigrant is willing to integrate (to some degree) into the culture of the host country, so “the expectation of integration is not unjust”. This presumption has a political consequence, for the rights reclaimed by immigrant minorities will be interpreted as ultimately aiming to integration with the dominant culture.

Integration of course does not imply the abandonment of the individual's original background. As Habermas observes in his essay “Struggles for Recognition in the Democratic Constitutional State”, contemporary democracies do not demand, for instance, that the immigrants stop speaking their native languages or that they give up on their religion. These demands seem relegated to a distant past, with Habermas mentioning Prussia imposing the Germanization of Polish immigrants under Bismark in late nineteenth century. At worst, they are hinted at by a certain anti-immigrant rhetoric: Nigel Farage's complaints about foreign languages being spoken on trains and in certain urban areas could be interpreted as a wish for such an abandonment. Let us accept that voluntary immigration licenses the presumption that the immigrant is willing to integrate. Still, we may ask: in how many cases is migration a genuinely voluntary choice? Two main counterexamples come to mind: refugees and (at least some) economic immigrants. When discussing the motivation refugees have to migrate to another country, it is difficult to describe their situation in a way that leaves room for a full-blown voluntary decision. This is because refugees do not seem to have any sensible alternatives to migration. They are forced to uproot themselves in order to fleet the bombings, the enemy occupations, the relentless persecutions. Similarly, many so-called economic migrants arguably do not decide to leave their countries in conditions ideal for a fully voluntary choice. Suffering irremediable unemployment, exploitation, or poverty seems to again make the decision to migrate more forced than freely chosen. This implies that the assumption of voluntary choice does not fully apply to a vast number of individuals that we would describe as “migrants” or “immigrants”, thus dramatically reducing the significance of the argument reconstructed above. What are the implications of all this? One possible reaction is to admit that, if leaving one's country of origin was not a fully voluntary choice, then we cannot infer that one has waived the right to be part of one's own culture. Indeed, Kymlicka goes as far as to concede that the subjects for whom migration was not fully voluntary retain the right to live and work within their culture, and that they “should, in principle, be able to recreate their societal culture in some other country, if so they desire” (p. 99). For Kymlicka, this implies that these groups have in principle a right to self-government comparable to that of minorities of non-immigrants in many contemporary democracies, like the Basque minority in Spain or the Quebecois minority in Canada (whose right to autonomy is advocated by theorists like Charles Taylor or Michael Walzer). Yet, how can this right be honoured, and by whom? The problem, Kymlicka explains, is that the right to be a member of one's culture is being violated by the government of the migrants' very home countries (through forms of political oppression or war) and there is no procedure at the international level for deciding which other government should guarantee this right. Plus, it seems improbable that a foreign country would offer its assistance on this score, since this would imply granting levels of political autonomy which transcend the usual integration measures. Ultimately, then, refugees and immigrants for whom migration were not a full choice are, and are regrettably likely to remain for a long time, the victims of an injustice: their right to live and work within their culture has been violated by their home countries and it is not possible to fully restore it in any other country.

1 Comment

Marc A.

3/1/2017 01:48:39 pm

Very interesting, Delia! :)

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

About UsThis is our project blog. Archives

November 2018

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed